Why You Shouldn't Listen to Your Body

You can do more than you think

At this point I can’t deny that my beat here encompasses two topics: software development and fitness. It feels embarrassing to put it like that, like I should move back to San Francisco or maybe to Austin and start wearing Allbirds, but what can you do. It’s not embarrassing the way I do it.

This post is about the latter subject, but first I’ll squeeze in a bit of the former: I recently published a guest article on the Expo blog about what it was like to come from a web background and build a mobile app. So check that out, and also install phomo if you’re on iOS, or sign up to test it (coming soon) if you’re on Android.

With that out of the way: I just wrapped up what has become an annual ritual of undertaking a pre-summer fat-loss diet. I’ve done this many times, refining the process a bit with each iteration, and I have accumulated some opinions — dare I say insights? — about the experience. I’m going to talk a little bit about the how of it, but focus more on the why, which I think is more interesting.

Before I continue, I’ll state the obvious: this post will discuss weight loss, calorie restriction, body measurements, things of that nature. If that sort of thing is upsetting to you, do not proceed. Also, I am not a doctor, dietitian, or personal trainer; I’m just some guy. This is not any kind of advice, let alone medical advice. By reading past this point, you agree that you are legally barred from getting mad at me.

My results

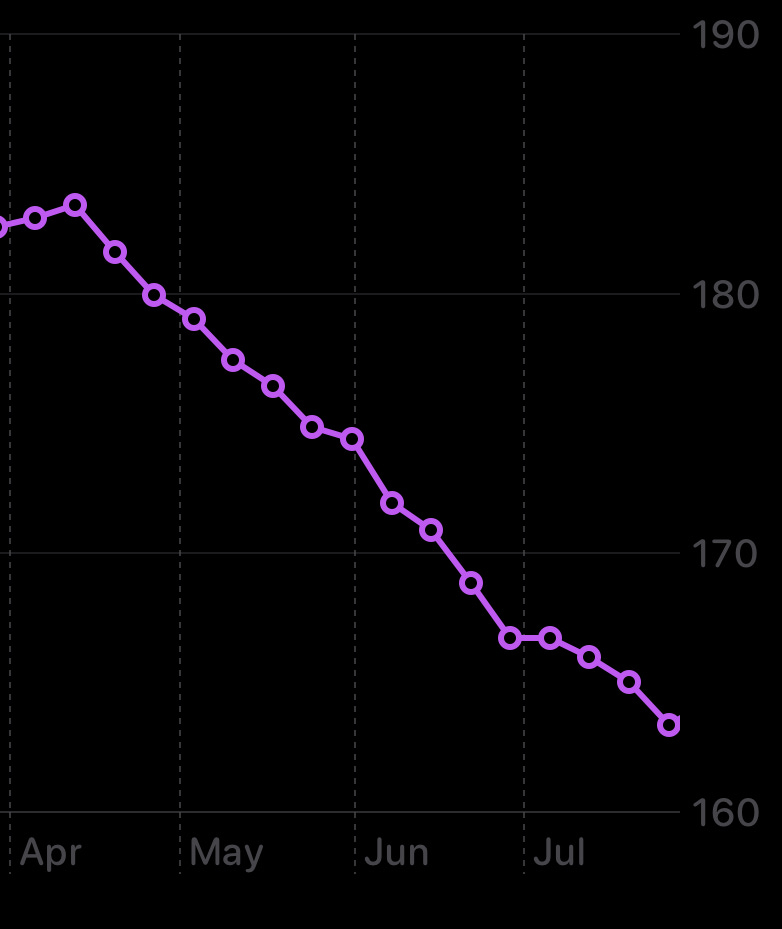

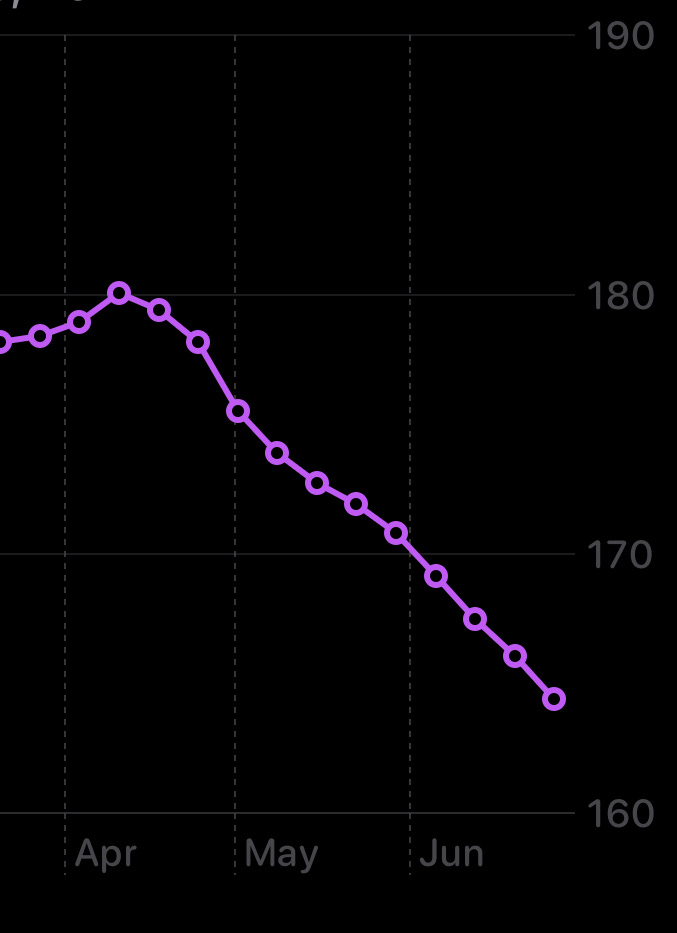

I’ll start with the numbers. I’m 39 years old and 6’ tall. My training approach has shifted more than once, but I’ve been lifting for 16 years. This year, I began my fat-loss diet on April 11th, at a bodyweight of 180.4 lbs. At that weight, my chest measured 44” and my waist 33.5”. It’s 10 weeks later, and I’ve lost 16.8 lbs. My chest now measures 43” and my waist 30.5”. For comparison, last year my results were similar, but my peak weight was a little higher, my chest a little smaller, my waist a little larger, and my fat-loss phase took longer (14 weeks).

My methods were standard — I counted calories and measured everything with a food scale. I was eating around 2100 calories/day for a while, then I cut back to around 2000/day. I weighed myself at the same time every morning. I ate at least 170g of protein every day. I didn’t change anything about my lifting routine, which I performed 4 days/week. After lifting sessions I would do a short ride on the stationary bike, and on 2 non-lifting days I would do a longer one. On Sundays I didn’t train. I tried to walk a lot. That’s it; no black magic or weird hacks.

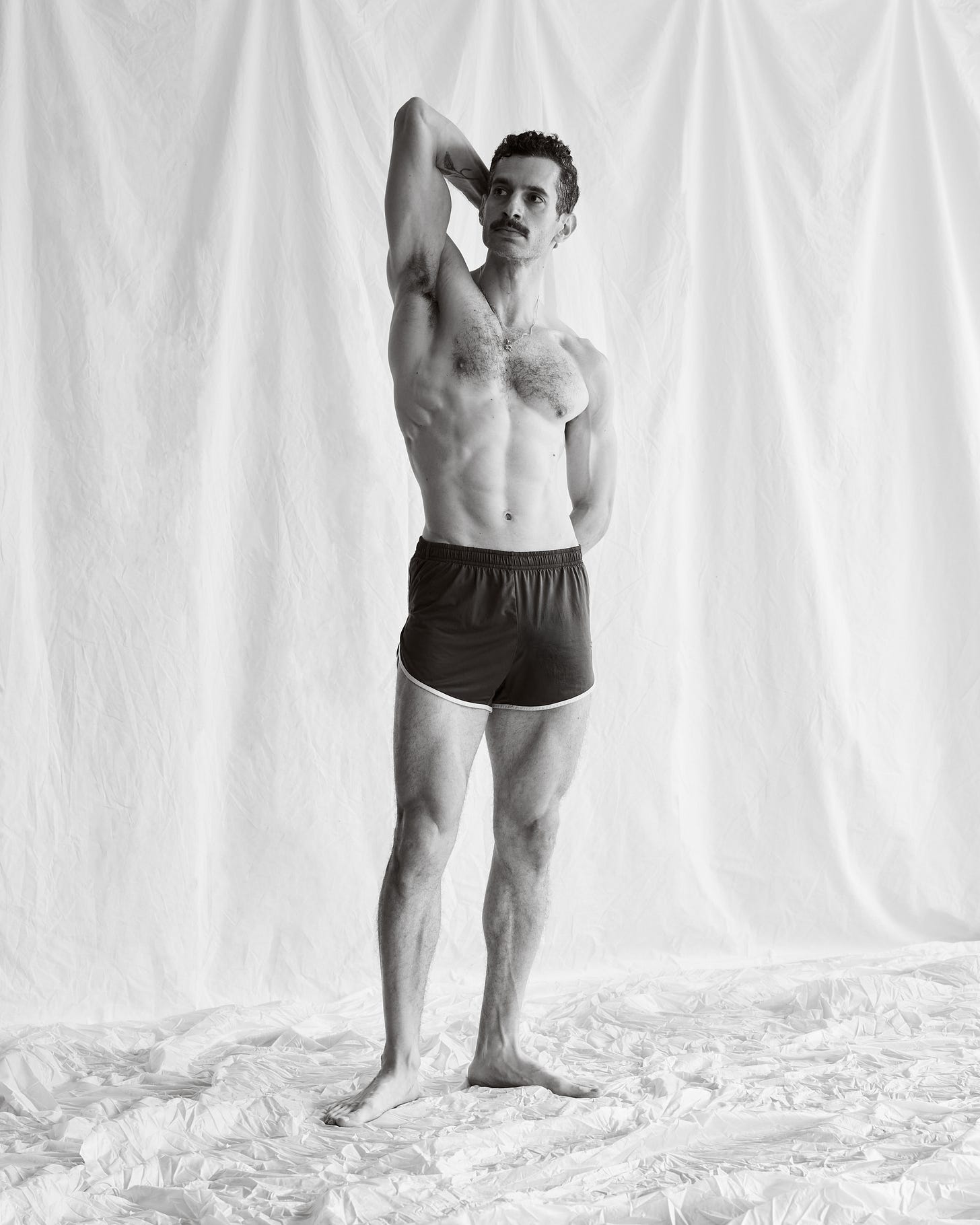

It’s hard to measure these things accurately, but I would guess I had a net gain of one or two pounds of muscle from last summer to this one, which I consider a success at this stage of my training life. I also consider it progress that I reached a similar level of leanness (still a long way from bodybuilding-contest lean, mind you) with a shorter dieting period. At the end of last year’s cut, I did a shoot with a photographer friend; this year I just took some selfies.

Terminology

Outside of a few scenarios — e.g. someone new to training, significantly overweight, or using exogenous hormones — a body can effectively build muscle or lose fat, but can’t do both at once. For this reason, someone past the beginner stage of training who wants to get both leaner and more muscular — or “tone up,” in colloquial terms — will tend to approach that goal in discrete phases: a bulking phase in which they add muscle and try to minimize the concomitant fat gain, and a cutting phase in which they try to lose fat while minimizing muscle loss.

This makes particular sense for a competitive bodybuilder, whose fundamental training goal is to be simultaneously very lean and very muscular. The extreme leanness required for the bodybuilding stage is not sustainable for more than a short time, so competitors will structure their cutting phase in the hopes of reaching peak condition precisely on the day of their contest. The timeline for contest prep varies, but tends to be in the ballpark of 12 - 16 weeks. When the contest season is over, they will enter an off season where their primary focus will shift from fat loss back to muscle growth. Then the cycle restarts, and it’s back to cutting down for the next contest. Outside of bodybuilding, an actor or model might follow a similar regimen in the lead-up to a shoot.

I’ve never competed in bodybuilding and have never been particularly interested in doing so. My livelihood doesn’t depend on me looking a certain way on camera. I have, however, found multiple benefits in taking a similar approach to training and diet; not only in terms of appearance and health, but also in a more spiritual sense.

Why bother?

Obesity is complex and multifactorial, but tends to be the result of gradual weight gain over a long period of time, like the proverbial frog in boiling water. According to a 2022 analysis in the Journal of Obesity, mean weight gain over 10 years in American adults is 6.6% of their initial bodyweight, with 16% of people gaining at least 20% of their starting weight by the end of a decade. So a 30-year-old man standing 5’9” and weighing 170 lbs — just a hair into the “overweight” BMI category — might reach 205 lbs by the time he’s 40, crossing over into the “obese” range. A yearly cutting phase isn’t just about looking good for the summer, it’s also a preventative measure.

When it comes to food, we in the developed world find ourselves surrounded at all times by excess and variety; and as for physical activity, more of us than ever can make a living without need for physical exertion. To recognize this fact is not to moralize about it; it is of course a good thing if resources are abundant and more people can live in comfort. But we must also recognize the potential hazards of this condition, physical and otherwise. Muscle doesn’t grow unless it’s pushed to its limit, and character growth is similar. When we have the option of living in an ambient state of comfort, we must occasionally seek out discomfort in order to keep ourselves sharp.

The cliche says “moderation in all things, including moderation.” The practice of moderation by definition necessitates its corollaries: the practices of indulgence and abstemiousness. Because without self-denial, how can we ever truly appreciate self-indulgence? Each only has meaning relative to the other. The fact that I spent 10 weeks of 2024 in an ascetic mode is precisely what allows me to be comfortable with being comfortable during the other 42. And while it never becomes pleasant or easy to go to bed hungry, knowing the end date helps me commit more wholeheartedly — a lot more can be endured when there’s an ending in sight. Conversely, I feel a similar reassurance during my more indulgent periods, knowing that they too will eventually be balanced by their opposite.

Sticking to the plan

There’s a beautiful simplicity in devising a plan and then sticking to it without deviation. I didn’t have to make decisions every step of the way. I didn’t have to agonize over whether I should eat X or if I shouldn’t eat Y; I just had to color within the lines. When someone hires a trainer or other professional helper, they seem to do it as much for the sense of duty that they hope the transaction will instill in them as for the quality of the instruction itself. The thinking goes something like: “I paid for this plan, so I need to stick to it or the money will be wasted; plus, if I fail I will be letting the trainer down.” But it’s possible to have the exact same attitude without involving another person or a monetary exchange. The trainer who decided on the plan is the past version of you, and the one you don’t want to disappoint is your future self.

And while many seem to regard the process of tracking their food as a stressful burden, I find that it provides reassurance and security. When I get to the end of the day and still feel hungry, I can look at my food log and know that I’m actually fine; even though I may feel as if I’ve eaten too little, and that I’m at risk of muscle loss and organ damage if not imminent death by starvation, I can see there in black and white that I actually ate plenty. And here lies the source of my semi-tongue-in-cheek title. When you’re on a calorie deficit, especially as you approach lower levels of body fat, you’re going to experience hunger and lack of energy. There’s no way around it. Hunger tends to make us less rational. When we’re not accustomed to these feelings because we spend all of our lives in a state of abundance, it is easy to interpret them as signs of impending doom; we’ll think we're starving and need to alter the plan. This is, of course, not true. It’s okay to feel hungry. You will survive. But you have to learn this by gradual exposure. Thus, self-denial leads to self-knowledge and eventually self-control.

Your body is a liar

“Listen to your body” is an aphorism with easy appeal. It suggests that our physical selves possess an instinctual wisdom from which our conscious minds have become disconnected. Perhaps in some contexts this is a useful framing, but I would suggest that the opposite framing can be more useful in others. Your body adapted to a state of scarcity which no longer exists for most of us, and so it lies to you. Or, if I were being a bit more circumspect, I could synthesize the two viewpoints by saying that your body doesn’t lie to you per se; it’s just that you’re ill-equipped to properly interpret your body’s signals. This truth is evident in a variety of physical disciplines. The average person holding their breath might start to feel starved for oxygen in less than a minute, but elite free-divers or similar athletes can hold their breath for 10 minutes or more. Some of the difference is down to physiological adaptations brought about by training, but some are psychological. The same applies to our ability to withstand other stressors, like cold, or heat, and certainly to intense exercise.

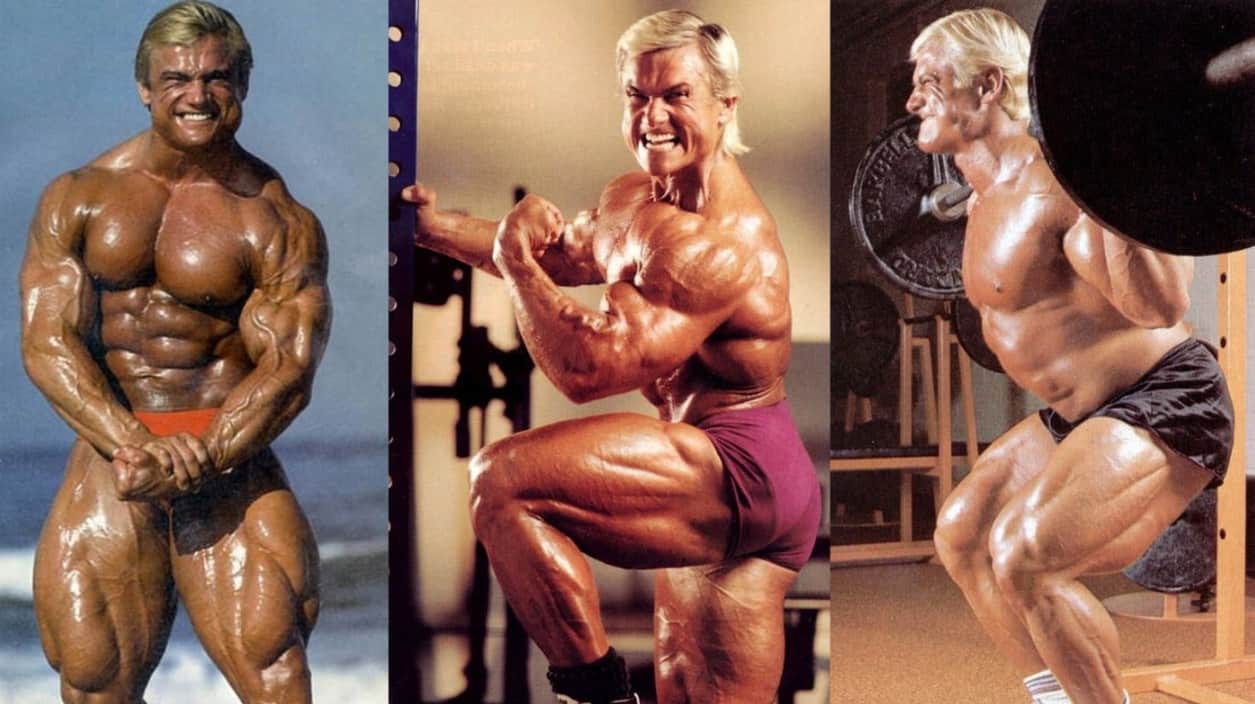

Tom Platz is a retired bodybuilder who competed during the 1970s and ’80s. He is famous for his extreme leg development and his intense approach to training. Tom said it like this: “When you think you’re done, totally done — you have at least five more reps.”

Many experienced lifters and coaches have described the phenomenon in similar terms. Arnold Schwarzenegger said, “The last three or four reps is what makes the muscle grow. This area of pain divides the champion from someone else who is not a champion.” There’s a particularly detailed elaboration of this concept from Alberto Nuñez, one of the world’s pre-eminent natural bodybuilders, who wrote:

…a certain level of discomfort is unavoidable when losing body fat. You will experience hunger, fatigue, and mood disturbance when using body fat to meet your body's caloric needs for extended periods.

Please view the situation from this perspective. Imagine a brand new trainee just getting started in the lifting world. When they perform leg extensions, they perform leg extensions not until muscular failure but until their brain tells them to stop. The leg extensions to their brain is … perceived as an attack on their safety. They stop at eight reps when realistically, they could have gotten at least eight more. Trainers who have experience with this demographic can vouch for this. When you perform leg extensions, not only has your brain learned to chill out … there is a connection/understanding to what happens over the long term when you push hard on this exercise. Not only can you achieve muscular failure, but it's a good day when you can explicitly feel the localized pain. A part of you even looks for trouble in these situations, and that same newbie lifter wouldn't understand how this could be. You are a simple masochist to them. That would be their perspective until they do it a few more times and eventually experience a similar cycle to yours as a trainee.

When it comes to dieting, the same evolutionary forces that make newbies stop prematurely stop on the leg extension are the same as the mind games that drive you a little crazy when dieting. Certain fat loss stages require poise that rivals the bravest of final reps on any given exercise. They can be annoying, like a noisy upstairs neighbor at night, or madly omnipresent, like a guilty conscience.

In other words, the difference between a beginner lifter and a more advanced one isn’t just about having more strength or better technique; it’s about the ability of the mind to properly interpret the body’s signals. There comes a point during a hard set of squats, for example, where it gets very uncomfortable. Your muscles are burning, you’re gasping for air. The less experienced lifter receives those signals and thinks “I have to stop now, or I’m going to get seriously injured.” The more experienced lifter gets the same signal, but they know it doesn’t mean they’re about to die; it means they’ve got five more reps.

Happy training.

I listened to a motivating YouTube video about having more reps in the tank and then promptly got stuck under the bar attempting an extra rep on the bench press haha

PED’s do some heavy lifting here for at least some of the example lifters given. In my experience if you lift natural push past the good sore and the good fatigue, especially if you have a spotter, but you better know to stop and listen to the bad soreness and fatigue and be sure to know the difference. And again have a spotter.