Drop the Routine

Does basketball make you taller?

Photos of the human body abound online. In the current era, the selfie may be the most common type of physique photo. Social media is, after all, largely about people saying “look at me” in one way or another. And internet culture being what it is, there’s a range of stock responses for a viewer to choose from in order to express approval. If you’ve looked below any body-focused photo posted to social media, you’ve seen comments like “body tea,” or “hottie alert” or simply “🔥.” But a common response that I find more interesting is “drop the routine,” along with its more specific variants, e.g. “drop the glutes routine” or “drop the shoulder routine.”

While on one level, “drop the routine” is just another way to say “you look good,” it says more than that. It also asks: “what’s your secret?” Even allowing that the question is intended as more rhetorical than literal, it still carries with it a series of assumptions: namely, that the subject’s physique was developed deliberately with exercise, and that someone else imitating that exercise routine could attain a similar physique. This logic seems straightforward enough on its surface, but is it sound?

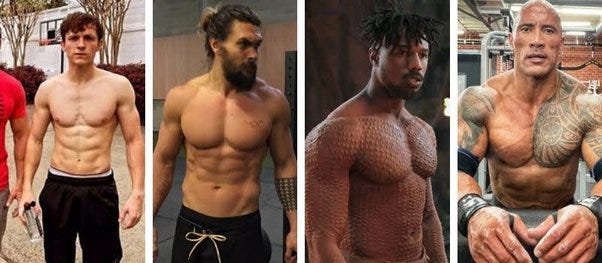

Athletes and Superheroes

This question lies beneath various perennial discourses; movie-star physiques, for example, are a frequent catalyst for conversations about what performers go through in order to build a screen-ready body.

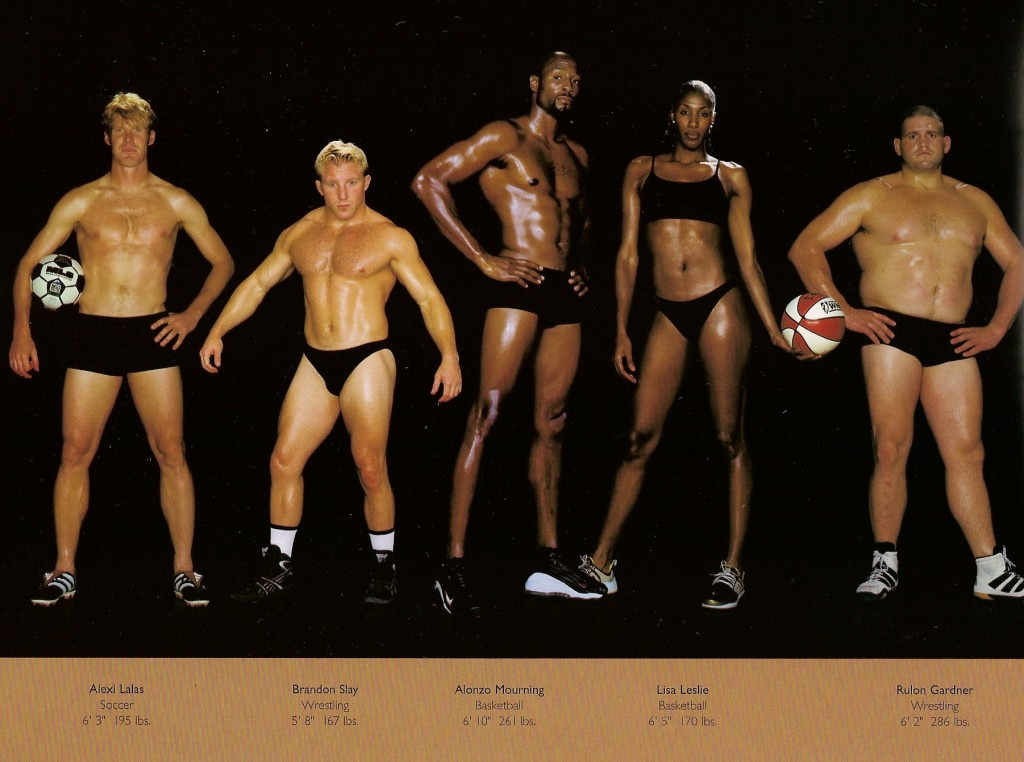

The Olympics are another, for obvious reasons. Whereas an American sports fan might avidly follow baseball, football, basketball, and hockey, the Olympics highlight elite athletes from a much more diverse range of disciplines. The way the athletes look may inspire awe and wonder, or perhaps curiosity — why do these athletes look so different from those? What competitive advantage does this type of physical development provide? The photographs of Howard Schatz and Beverly Ornstein frequently crop up online as an illustration of these concepts. Their book Athlete, published in 2002, contains a number of compositions which juxtapose athletes from different sports in a way that makes them look almost alien to one another.

The competitors of some sports tend to align more closely with conventional standards of attractiveness, and are thus more likely than others to inspire imitators; every time elite mens’ gymnastics gets mainstream exposure, some number of young men will decide to take up gymnastics training. Not necessarily because they want to accomplish gymnastic feats, but because they want a gymnastic physique.

What’s the Issue?

I think people being inspired to exercise is a good thing, regardless of whether the source of inspiration is a movie star, a professional athlete, or a social media influencer. But focusing on physique rather than performance, and misunderstanding the nature of the relationship between the two, can set someone up for frustration and failure.

The first and most significant aspect of the misunderstanding at play here is selection bias. The subtitle of this article is a tongue-in-cheek illustration of this error. The average height of a player in the NBA is around 6’6”, which is some 9” taller than the overall average for American men. However, we all understand that playing basketball doesn’t make people taller, but rather that being tall confers an advantage in basketball. This is easy to understand because it’s obvious that height isn’t a feature that can be developed via training. But with other aspects of the physique, the nature of cause and effect gets more complicated.

Immutable Structures

To return to the previous example; since Olympic gymnasts have impressive arms, does that mean that training gymnastic skills is the best way to build impressive arms? The answer is no, for lots of reasons. For one, let’s return to the example of height and basketball. For a male gymnast, being short often confers an advantage. Jake Dalton, pictured above, is billed at 5’6” and 145 lbs, a fact belied by photos of him standing alone and flexing, where he looks massive. Shorter limbs means smaller levers, which makes many gymnastics skills easier to perform. A shorter limb will also appear thicker than a longer one with the same amount of muscle.

We can train to build muscle or lose fat; we can choose to emphasize particular muscles or neglect others; but we can’t change, for instance, the lengths of our limbs relative to our torso, or the width of our clavicles relative to our hips. We also can’t change our muscle insertions, which have a major impact on both function and appearance. As with many aspects of the human body, what qualifies as “normal” isn’t a single value but a range. Different insertion points are why one person’s biceps or calves, for example, might look more “peaked” than another’s, even at similar levels of overall muscle and body fat.

The above image was posted to reddit by a user wondering how to change the way his biceps look. The response was a resounding consensus: you can’t. While training can make muscles grow, and diet can lead to fat loss so they’re more defined, there is no exercise routine that will change the basic shape or length of a muscle. Routines aimed at women are particularly guilty of claiming things like being able to “lengthening” muscles, but no such thing is possible.

Another factor that’s particularly salient for women is body fat distribution, as they carry more essential body fat than men, and the particular way it accumulates plays a larger role in conventional standards of attractiveness for them. While the overall amount of body fat a person carries is changeable via diet and exercise, body fat distribution tends to be determined by hormone levels and other less-changeable factors. Women generally tend toward what’s called a gynoid fat distribution, as opposed to the android fat distribution seen in men, but there will be individual variation.

Having a round, pronounced butt has been in vogue for women in recent years. As a result of this demand, there’s been a whole crop of influencers trying to teach women how to build a bigger, perkier butt. And there are good ways to do that; the glutes are powerful muscles that can be developed via resistance training. But without even mentioning the influencers who flaunt their physiques while omitting that they’ve had cosmetic surgery: the butt is a major site of body fat accumulation. Even in a very fit individual, unless they’re at bodybuilding-competition levels of leanness, the specific appearance of their butt will have a lot to do with the way they carry fat. Some women just have more in their hips and less in their waist, which is totally unrelated to what they’re doing in the gym. Women wanting to look like them aren’t going to get there by imitating their training routines, which may in fact be totally ineffective at producing the desired result.

Training Responses

While top athletes may achieve more in part because they’re more dedicated than average, some people also experience larger adaptations than others in response to the same type of training. Some of the mechanisms behind these disparities are known, others still being discovered. There is a large range of “normal” for hormones like testosterone, which plays an important role in development of muscle and strength.

Furthermore, individual muscles may be made up of different fiber types. Some types of muscle fiber are better for endurance, others for strength; the latter have more potential for hypertrophy. The distribution of fiber type may change due to training, but has a major genetic component as well.

The top performers in a given sport will tend to have a distribution of muscle fibers that’s favorable to their discipline. They are genetic outliers; they are simply built different. And that difference caused them to become successful at their sport rather than the other way around.

Herschel Walker, pictured above, is one famous example of this phenomenon. An extremely successful athlete with an impressive physique, Walker has famously claimed that his workout consists only of performing thousands of pushups and sit-ups every day, and his diet is largely bread and salad. Maybe he’s not telling the truth, but let’s assume he is. Would it be a good idea for a young athlete who admires Walker’s athletic achievement and physique to imitate his routine? While there are certainly worse things they could do, it’s probably very far from the optimal path. Walker is simply an extreme outlier, a hyper-responder, and while his results are interesting, they don’t offer much in the way of a blueprint for a more typical individual.

Beyond Sport Training

There was a time when an athlete’s training regimen rarely extended beyond practicing their own sport; their bodies were developed almost entirely on the field, rather than in the gym. Early NFL players, for example, avoided the weight room out of fear of becoming “musclebound.” Those days are long behind us, though. High-level athletes will almost universally spend time in the gym, working on developing their physical attributes separately from practicing their specific sport. For many different types of athletes, this means lifting weights.

While it may not make up the majority of their training, gymnasts, sprinters, throwers, etc. all lift weights. They do it because getting stronger in specific ways makes them better at their sport, and lifting weights in one form or another is the safest and most efficient way to increase strength.

For another illustration, look at the planche above. Every athlete who can planche will exhibit visible biceps development. But there are lots of bodybuilders, for example, with similar biceps development who can’t planche, and training for planche is far from the optimal way to develop bigger biceps. So we can say that while there is a relationship between the planche and biceps development, it’s not exactly a straightforward one. Or: If you want to do what an athlete does, you have to practice their sport. But if you want to look the way an athlete looks, you should train like a bodybuilder.

Attaining vs. Maintaining

I’ve been training consistently for 16 years. Most of that time I’ve been focused on strength / hypertrophy, although for a couple of years I was very focused on gymnastic strength. That’s why I can still knock out controlled muscle-ups on rings, or perform a decent tucked front lever or planche hold. But it’s important to remember that strength, muscle, and skill are all easier to maintain than they are to build. And so the routine I perform now is often very different from the one I was following when I first developed a particular ability.

The video above shows me performing a 170 lb overhead press at a bodyweight of around 165 last month. Although I’ve done heavier presses in the past, both in absolute and bodyweight-relative terms, I was still proud of this (although I think I could’ve hit 175 that day if I’d chosen my attempts better). In the overall gym-going population, pressing one’s bodyweight is pretty rare. But I developed my strength in this movement many years ago, and haven’t improved it much in a long time, because the standing barbell press hasn’t been part of my training for awhile. I have different goals now than I did then, and since this movement doesn’t help me achieve them as well as others, I don’t do it. So you can understand why me detailing my routine wouldn’t have much relevance here.

Similarly, I’ve been asked to divulge my ab routine, presumably because, if you catch me at the right time of year, I exhibit a good amount of ab definition. But I don’t have an ab routine; in fact I don’t train abs at all, and never really have. My abs look the way they do because they’ve developed incidentally, while performing other movements like squats, deadlifts, and presses; because I’ve dieted down to a low level of body fat; and because of my body’s particular structure, which I was born with.

If I were a less scrupulous individual, I might try to sell a workout program using my own physique or achievements in the gym as marketing. To maximize social media engagement, I might want to make the routine I’m selling as eye-catching as possible, so I might include a large and varied selection of movements. But the routine I’d be selling, and the movements I’d be doing to market that routine, would have very little to do with how I actually developed my physique, which was far more repetitive and mundane. This is a common phenomenon among social media influencers.

Bottom Line

The relationship between genetics, exercise, and physique is a complicated one, but there are a few things we can say for sure. It’s always advantageous to have a clear understanding of one’s goals, whether they’re about achieving a skill, improving a particular aspect of performance, or looking a certain way. The optimal paths for achieving these various goals may have a lot of overlap, but will often diverge as well. To improve performance in a given discipline, there’s no getting around having to train specifically for that discipline. But getting better at a particular athletic discipline may or may not make you look more like the top performers in that field. The way you look, the way you perform, and the way your training influences those factors will depend heavily on things outside of your control, and focusing on elite performers can easily lead to incorrect conclusions about how to achieve our goals. Working hard in the gym is a good idea not because it can make you look like someone else, but because it can make you into a better version of yourself.

Awesome article there was a time in my life as you know when I worked out frequently. Unfortunately, some setbacks have limited that my goal is to get back to some semblance of a work out routine. What the mind can conceive the body will achieve

I thought this sounded familiar and I couldn't place it but I believe I heard you discuss this on Joshua Citarella's "Doomscroll" podcast. I've been thinking of this type of stuff ever since. Glad I was able to see a more detailed description.